The United States would still have a prison problem if it did away with its nonviolent prison sentences. That said, the measure would be a massive boost to a recently trending down prison population.

In 2018, the American federal and state prison population stood at roughly 1.47 million people, according to a Justice Department report. With 427 sentenced prisoners per 100,000, much of America’s prison population is composed of minorities and disproportionately affects Black communities. However, these figures understate the impact felt across the board, and especially in marginalized communities.

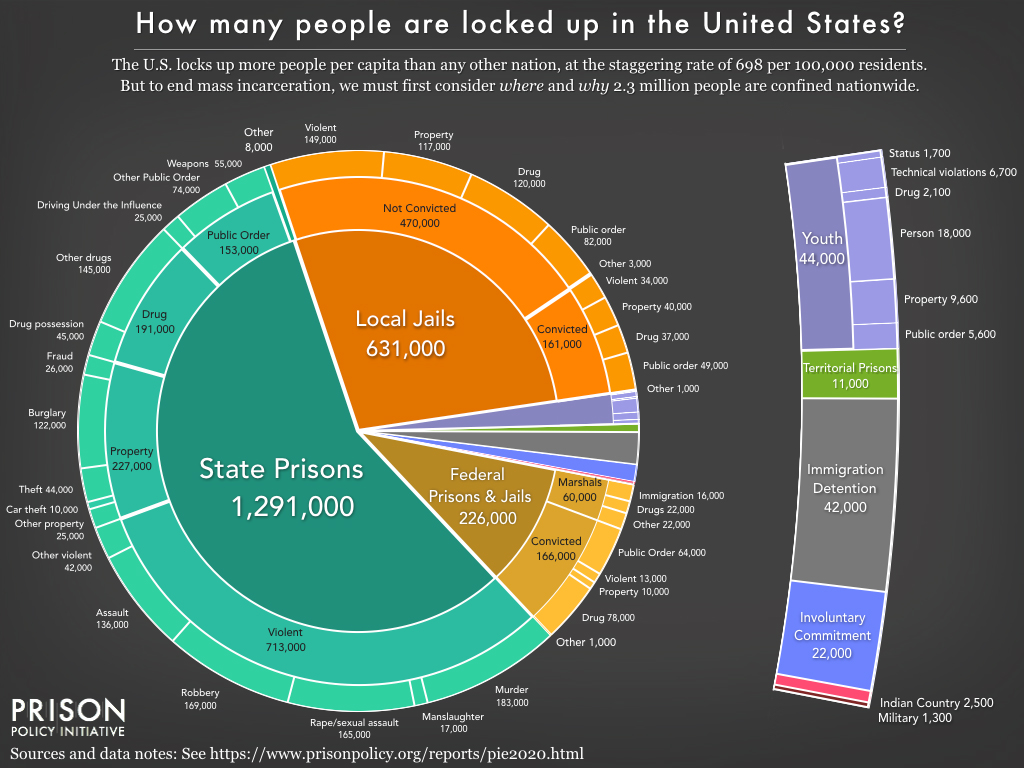

A 2020 report released by the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) accounted for more than just the imprisoned. Its total includes figures for juvenile facilities, local jails, immigration detention centers, military prison, Indian Country jails, and as well as psychiatric hospitals and other forms of incarceration. In total, the PPI report concluded that America’s prison population stands at around 2.3 million people.

Drug arrests make up a significant portion of those in the system, and the country is paying top dollar for every one of them. Data from the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) claimed that the war on drugs currently costs the United States roughly $47 billion each year.

In their report, Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner wrote, “Drug offenses still account for the incarceration of almost half a million people, and nonviolent drug convictions remain a defining feature of the federal prison system.” They added, “Police still make over 1 million drug possession arrests each year, many of which lead to prison sentences.”

The Effect On Nonviolent Offenders

Those sentenced to prison stints are then often locked into a lifetime of some form of mass incarceration. In a 2014 interview with the PBS series Frontline, multi-hyphenate legal and education expert Michelle Alexander explained the effect mass incarceration has on an individual.

DPA data found the one in 13 Black people of voting age are denied the right to vote.

Alexander, the author of The New Jim Crow, explained:

“[Mass incarceration] is the process by which people are swept into the criminal justice system, branded criminals and felons, locked up for longer periods of time than most other countries in the world who incarcerate people who have been convicted of crimes.”

Todd A. Spodek, a New York City criminal lawyer, said nonviolent offenses had flooded prisons in recent decades. The rush of these types of now-imprisoned criminals led to a lack of segregation between the violent and nonviolent, according to Spodek.

The attorney discussed the effects this often creates inside America’s prisons. “This results in fights, treatment concerns, and lack of adequate supervision.” Spodek added, “By incarcerating nonviolent, particularly low-level drug offenses, you are taking space for a violent individual and ultimately costing the tax paper more money.”

After prison, life can remain hellish. As Alexander told Frontline in 2014: “[Released prisoners are] then released into a permanent second-class status in which they are stripped of basic civil and human rights, like the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to public benefits.”

Abraham Villegas, founder of the group The Medical Cannabis Community, elaborated to Green Flower about the effects of mass incarceration after the prison sentence ends. “Criminal records for these already disadvantaged minorities means increased likelihood of future arrests, lesser career prospects, and various other negative effects on their lives — all for a commodity that is now being profited off of by the same society that imprisoned them for it.”

The ramifications extend beyond the individual, often reaching into their family and community as well.

The Effect On Communities & Families

The lasting effects of the drug war often reverberate long after the sentence has supposedly ended. In many ways, the system is working just as it was designed.

On Frontline, Alexander explained that some components of the system of mass incarceration began in the 1950s and ‘60s during the law-and-order era of the time. The legal decisions largely stemmed from segregationist worries over nonviolent protests and demonstrations, calling the actions what Alexander described as “reckless behavior that threatens the social order and demanded…a crackdown on these lawbreakers, these civil rights protesters.”

Such actions were confirmed in recent years when the Domestic Policy Chief to President Richard Nixon, John Ehrlichman, told Harper’s that the war on drugs was an act to suppress the growing activity in the Black and hippie communities.

Lawyer Spodek highlighted the lasting impact the war on drugs has on communities, particularly those of color. Citing an ACLU report that found people of color are 3.64 times more likely to be arrested for possession, the managing partner told Green Flower, “The impact of an arrest and prosecution for any crime is significant, particularly on the individual’s family.” Spodek would add, “These arrests have a trickle-down effect on the individual, their family, and communities.”

DPA findings report that one in nine Black children have an incarcerated parent. Hispanic families see a ratio of one in 28, while White families are one in 57. With a parent in prison, children face more significant risks of adverse impact on their mental health, social behavior, and educational prospects in the years ahead.

He further clarified that “Studies have shown that residents of neighborhoods with high incarceration rates endure disproportionate stress, due to disrupted social and family networks alongside elevated rates of crime and infectious diseases like COVID-19.”

Calls For Change

The recent rise in protest, demonstrations, and activism across the country represent the latest effort to end the war on drugs, and the disproportionate policing of Black and other minority communities.

As the 2020 PPI report stated, “Nevertheless, 4 out of 5 people in prison or jail are locked up for something other than a drug offense — either a more serious offense or an even less serious one.” It explained what it considers necessary steps going forward.

The report would state, “To end mass incarceration, we will have to change how our society and our justice system responds to crimes more serious than drug possession. We must also stop incarcerating people for behaviors that are even more benign.”

As the data shows, the incarceration goes beyond behaviors and reveals that race often plays an integral role. It must be addressed on all its painful levels. While it won’t be a fix-all, cannabis reform could do its part to reverse the long, ugly history of oppression in this country for Black individuals as well as all the other people in prison merely for marijuana.